This 41 page report is also available in PDF format.

E-Government and Democracy

Representation and citizen engagement in the information age

By Steven L. Clift

This article is based on research provided to the United Nations – UNPAN/DESA for the 2003 World Public Sector Report: http://unpan.org/dpepa_worldpareport.asp

Public Version 1.0, Released February 2004

Table of Contents

- Summary

- Introduction

- Initial Conclusions

- Research Trends

- Democratic Outcomes

- Trust and Accountability

- Legitimacy and Understanding

- Citizen Satisfaction and Service

- Reach and Equitable Access

- Effective Representation and Decision-Making

- Participation through Input and Consultation

- Engagement and Deliberation

- Conclusion

E-government and Democracy

Representation and citizen engagement

in the information-age

Summary

Leading governments, with democratic intent, are incorporating information and communication technologies into their e-government activities. This trend necessitates the establishment of outcomes and goals to guide such efforts. By utilizing the best practices, technologies, and strategies we will deepen democracy and ensure representation and citizen engagement in the information age. It is upon this foundation that opportunities for greater online engagement and deliberation among citizens and their governments will demonstrate the value of information and communication technologies in effective and responsive participatory democracy.

Introduction

E-government and democracy, fused together, are one piece of the e-democracy puzzle. Whether it is online campaigning, lobbying, activism, political news, or citizen discussions, the politics and governance of today are going online around the world. What is unknown, is whether politics and governance “as we know it” is actually changing as it goes online.

From the perspective of each government, civil society, or business organization, it is relatively easy to explore our institutional role in building participatory democracy online. Taking the whole situation into account is the difficult challenge. We are not building in a vacuum, nor are we developing our efforts in a constant environment. In the end, the only people who are experiencing the totality of the emerging democratic information-age are citizens or e-citizens.

This research takes a comprehensive look at the democratic outcomes that can be sought by government, civil society, and others in order to deepen and enhance participatory democracy online. With a particular focus on e-government and democracy, the vision for online-enhanced participatory democracy, or “e-democracy,” relies on an incremental model of development that involves the many democratic sectors and their institutions across society.

The democratic institutions of government (including representative bodies and elected officials), the media, political parties and interest groups, as well as citizens themselves, are going online across the world. The question is not – will we have e-democracy? It exists today based on the positive and negative uses of this medium by democratic institutions, non-democratic actors, and citizens. The real question is – knowing where we are and what is possible, what kind of e-democracy can or, better yet, should we build?

Governments, as a public institutions and guardians of democracy, need to play a proactive role in the online world. First, they need to maintain existing democratic practices despite pressures coming from the information-age. Second, they need to incorporate and adapt online strategies and technologies to lead efforts that expand and enhance participatory democracy. Deepening citizen participation in democracy is vital to ensuring that governments at all levels and in all countries, can both accommodate the will of their people and more effectively meet public challenges in the information-age.

The path toward information-age democracy is a deliberate one. Political and social expectations and behavior change too slowly to expect information and communication technologies (ICTs) to give us a direct, uncomplicated path to greater participatory democracy. The is no “leap frog” path that easily leads to responsive governance that supports human and economic development. The e-democracy path needs to be mapped out, so it can be traveled with confident and assured steps.

This article explores the following ICT-enabled path with the governmental perspective in mind:

- Understanding “as is” political and governance online activity by establishing baseline measurements, including current citizen experiences.

- Documenting government best practice examples and the sharing of results.

- Building citizen demand and civil society activity.

- Spreading practice and creating more deliberative options and tools.

Analysis focuses on the second path, comments on the third, and based on that analysis, explores the fourth. This pragmatic approach is essential to developing sustained activity across our many and diverse democracies. Today, it is very easy to dismiss the democratic potential of the Internet because it did not deliver the revolution hyped in early media coverage. This paper looks beyond the hype.

Even in the most democracy-friendly places, steps one and two are stumbling blocks. Tools being developed for step four are for the most part outside of government. Overall, the foundation of understanding, government practice, and citizen experience has not been fully explored or developed. Efforts to build ICT-enhanced participatory democracy may be delayed by those in power, if change promoted from the “outside” is highly politicized. Slow uptake is also possible if the use of ICTs for meaningful democratic participation is not seen as inevitable, even if a government agrees in principle that new forms of participation are desirable.

Only by demonstrating that participatory governance leads to better democratic outcomes – helping society develop and meet its political, social, economic and cultural goals – will ICTs in political participation become inevitable, well resourced, and fully implemented.

Based on my decade of observations online and in-person visits to 23 countries, the potential benefit of ICTs in participatory democracy continues to grow around the world. Everyday, more citizens use the Internet around the world. More are applying it toward political and community purposes than the day before. Everyday, another government adds a new online feature designed to bring government and citizens closer.

As this potential grows, the reality is that what most people and governments actually experience remains little changed. If citizens and governments are currently satisfied with the current state of their democracy, there is little incentive to accelerate or invest in efforts that seek to improve governance and citizen participation. However, if there is a desire to improve engagement, the often cost-effective potential of ICTs should be applied toward this goal along with complementary strategies and reforms. As some had mistakenly hoped, the existence of new technology does not necessitate its use nor does it change the innate behavior of citizens, politicians, or civil servants. For the most part, we are not experiencing an inherently democratic and “disruptive technology” that is forcing revolutionary change.

Welcome to the democratic ICT evolution. Therefore, from an incremental evolutionary perspective, e-government already impacts participatory democracy in the following areas:

1. Where there is a historical, political or cultural basis for a more active civil society and government facilitated participatory and consultative activity.

2. Where the technology has allowed emerging interest in participatory democracy to come into fruition at a lower cost that avoids economic or government controls on traditional media. This assumes that the legal or personal security consequences of online political and media activities do not outweigh the perceived benefits of those taking risks.

3. Where the competitive political environment encourages the institutions of democracy from parliaments, elected officials, the executive, political parties, interest groups, and the media to bring political activities online. These activities often promote participation to the extent that they further the interests of each institution.

Again, based on my observations, I predict that in the near future the democratic ICT evolution can be taken further and deepen democracy in the following places:

1. Where governments undertake e-democracy/e-participation as well as general civic engagement/consultation policy work and allocate specific resources to such activities.

2. Where e-government service delivery efforts and public portal developments reach a high state of development and maturation. This makes it obvious that previous government policy comments about the democratizing potential of the Internet must receive full consideration or be dropped. When complemented by top-level political direction and some manifestation of “demand” from citizens, e-democracy in government will have significant potential.

3. Where civil society led efforts work to establish information-age public spheres or online commons specifically designed to encourage political and issue-based conversation, discussion, and debate among citizens and their governments. The online public sphere needs to play a public agenda-setting and opinion formation role. With proper resources, structure, and trust, it can play a deliberative role in public decision-making.

4. At levels of government closer the people. It is well known that people tend to participate if they feel their participation makes a difference. At more local levels of government, the use of ICTs in governance will be easier for a broader cross-section of citizens to see the results of their enhanced participation. Also at this level, citizen-led efforts can have the larger lasting impact on public agenda-setting from the “outside.”

To date, much of the research on the democratic, political, and governmental impact of ICTs has focused on:

1. Online activities, particularly comparisons of web site features of political institutions such as campaigns and political parties.

2. Development of e-government services from a planning and strategy perspective or a focus on public administration reform.

3. Surveys of citizens about their political online activities. These surveys are creating a partial baseline of activities for ongoing measurement. There are far fewer surveys of elected officials, government decision-makers, and political elites including journalists.

4. The practices of “online consultation” or “e-rulemaking” with an emphasis on best practices and lessons learned.

5. Pre-1995 research focused on “teledemocracy” and the possibilities for technology-enhanced or enabled direct democracy.

As of late, emerging research is:

6. Exploring the online public sphere and opportunities for deliberative democracy as applied online.

7. Focused to a small but important degree on e-parliaments. Little research is exploring the role of the ICTs in state legislatures, city councils, and other representative bodies.

8. Making the institutional “amplification” argument[1] that may replace the contrived cyber-optimist/pessimist approach to analyzing the impact of the Internet on political behavior.

9. Being supported by general new media and Internet research. Research on usability needs to inform e-government development in particular.

10. Research compiling “what if” speculation continues to be plentiful. The questions being asked are often too general to be useful in the field by practitioners.

Overall, the revolutionary expectations created across many industries by the “dotcom Internet-era” obscured the evolutionary processes that are actually at work.

Ultimately, qualitative and quantitative research projects measuring specific ICT-based strategies that are designed to achieve specific democratic goals are required. You do not make bread by simply pouring water into a bowl of flour. You mix it, activate it, kneed it, add local flavors and ingredients and bake it. You have a recipe.

If your democratic goal is to increase turn out at public meetings, you might experiment with three online techniques, combined of course with traditional outreach. Then based on the results, you would determine which ICT-infused ingredient should be added to your recipe and passed on to others. This is granularity of comparative research required to make a meaningful contribution to the success of e-government and e-democracy efforts. Based on my ten plus years in the field and extensive literature reviews, this research does not exist.

The future of democracy and e-government will be determined by development of a cookbook, supported by research, with the best e-democracy recipes and notes on regional and cultural specialization. This cookbook will only feed the citizens hunger for more meaningful and effective participatory governance if the cookbook is used in a kitchen of democratic intent. This democratic situation right now is like a Windster Range Hood which is strong and firm with its quality. I like it very much. I mean for the product reference, just read Windster range hood review.

Based on the limited research that evaluates the impact of the best-practice use of ICT tools and strategies in efforts to improve democracy, the next section will build evidence through a review of “evolutionary” case examples tied to a discussion of democratic outcomes.

Each evolutionary ICT practice and tool needs to be considered in the context of democratic goals (more is good, more effective is even better). The democratic goals to connect to e-government efforts and practices include:

1) Trust and Accountability

2) Legitimacy and Understanding

3) Citizen Satisfaction and Service

4) Reach and Equitable Access

5) Effective Representation and Decision-Making

6) Participation through Input and Consultation

7) Engagement and Deliberation

Using ICTs to promote, as stated in the United Nation’s Millennium Declaration, “democratic and participatory governance based on the will of the people,” may lead to more responsive and effective government. It also inherently suggests reform and a dynamic different than the automation or reform of existing services.

Within government and in civil society, this is not a challenge for technologists to meet alone – these are primarily political questions and options raised by ICTs. In reality, this requires democrats informed by technology and technologists informed by democracy to craft an information-age democracy that not only accommodates the democratic will of the people, but also furthers the public good in an effective and sustainable manner.

With the great diversity in political systems and definitions and practices of democracy, it is impossible to determine the single best solutions for every objective. Those who are waiting for the best solution will be waiting a long time. Assuming, however, that a democratic objective exists, there are probably 5 best choices along with 95 likely mistakes to avoid related to each possible initiative. A review of ICT-based case examples connected to an elaboration of the importance of democratic goals will help government and others navigate their options and avoid as many mistakes as possible.

The decline in the public’s trust in government is a widely known global trend. It is of great concern to governments and those working to strengthen civil society. Accountability is the simple notion that governments and civil servants can be held accountable for their actions, processes, and outcomes.

The March 2003 OECD policy brief on the “e-government imperative” stated:

E-Government can help build trust between government and citizens

Building trust between governments and citizens is fundamental to good governance. ICT can help build trust by enabling citizen engagement in the policy process, promoting open and accountable government and helping to prevent corruption.[2]

This and a number of reports suggest that openness and transparency can be furthered through e-government, particularly in developing countries as it relates to anti-corruption measures.

ICT strategies and applications seeking to achieve the many democratic outcomes identified in this paper may contribute to an overall increase in government trust, but with the state of cynicism about government, results may be hard to measure. There is no one “trust-building” ICT application.

Why would governments want to identify building trust and accountability as an e-government goal? For those who promote cost savings or citizen service convenience as the top e-government drivers, telephone survey results from the Center for Excellence in Government provide a message from the public – we are looking for ways to rebuild our trust in government and e-government is a path we are willing to take to get us there.

Their survey asked the public to choose the one possible positive benefit would they “think would be the most important:”

28% – Government that is more accountable to its citizens

19% – More efficient and cost-effective government

18% – Greater public access to information

16% – Government that is better able to provide for national and homeland security 13% – More convenient government services

6% – None/Not sure[3]

The results have been relatively consistent over three years. With the release of the first results in 2000, a number of e-government leaders were surprised at the ranking. Up until that point, the e-government message going back many years was strongly focused almost exclusively on cost-savings, efficiency gains, and citizen convenience. The “public access to information” and “accountability” outcomes point toward the need to use ICTs in ways that promote trust in government.

From a comparative perspective, these questions (without the homeland security option) were asked in Japan in December 2001 via a home delivered survey. The results were similar:

31% – Government that is more accountable to its citizens

16% – More efficient and cost-effective government

15% – Greater public access to information

27% – More convenient government services

11% – None/Not sure[4]

The biggest difference between that and the 2000 U.S. answers is that that more Japanese indicate a higher first preference for more convenient government services. Again, accountability ranked first among the citizen-selected options in both countries.

The reasonable question from e-government leaders and vendors in response to these surveys is – What is an ICT application that delivers government accountability? Where are the resources to pay for a priority that has not been presented to decision-makers in the past? How do we know that e-government can deliver results in this area?

The answer is that citizens probably want a combination of all these benefits. Applications that deliver accountability and access to information along with efficiency and convenience will win citizen approval. Therefore, the way forward is to adapt e-government solutions by adding accountability features that directly address the more comprehensive and expanded goals of e-government.

The building of democratic trust via e-government can also be complemented by efforts that leverage existing trust in government to increase citizen comfort with the usage of the service transaction components of e-government.[5] Another survey by the Center for Excellence in Government found that e-government users in the United States have greater levels of “high trust” in government compared to non-e-government online users (36% versus 22%).[6] Use of e-government is not necessarily what caused this increase in trust, but it is a factor worth exploring in future research. In the end, increasing people’s confidence and trust in government through e-government is an outcome worth measuring and pursuing.

Note: Case studies complement each section and are integrated into the overall flow of this paper.

Case 1 – Policy Leadership

E-democracy policy leadership represents the government led review and adoption of policy options that guide programmatic democracy and e-government positions, requirements and initiatives. Related policy terms include e-participation, online consultation, e-governance, etc.

Governments in a few countries, states and provinces are identifying their own more comprehensive e-democracy/e-participation policy frameworks or programs. This includes places like the United Kingdom, Queensland, Australia, and Ontario, Canada. Central to successful policy efforts are political leadership and the involvement of decision-makers.

For the most part, government e-democracy policies and goals are not articulated like those related to e-services. If e-democracy is not part of what is evaluated or budgeted, then the administrative and resource priorities within agency e-government efforts will not likely address the e-democracy responsibilities of governments.

Non-coordinated agency-by-agency approaches to e-democracy have limited value, because the assumptions of efficiency and cost savings cannot be easily translated from the dominant services framework. Those versed in e-government talk of security, convenience, process reform, and transactions face new notions of participation that require openness, information access, and transparency. Democracies that work well are always adjusting their “optimal public input caused inefficiency” required for government to reach more effective and responsive decisions. By its very nature public participation takes time. To the full-time e-government manager or policy maker, these democratic requirements may seem contrary to their critical mission requirements. This points to a division of policy responsibilities to ensure that a balanced e-government with democratic elements emerges.

Government-wide e-democracy policies may create the economies of scale for the policy development and ICT-tool creation. It will create a framework for action and the exchange of best practices among government agencies and other levels of government. As policy is put in place, adding the e-democracy members to the e-government team will smooth implementation and insure that e-democracy practices follow policy.

Formal or significant consideration of the e-democracy opportunity or responsibility within government is rare. Most governments mention the democratizing potential of ICTs in their e-government plans, but few have staff dedicated to monitoring the issue or developing proposed policies. However, where governments have staff dedicated and policies designed to enhance participatory governance generally, those efforts can leverage ICTs to re-ignite their missions.

E-democracy policy or not, the infusion of ICTs into the traditional activities of democracies continues to grow and will be explored through out this article. My sense is that while policy efforts can bring future access to resources and jump start activity, in some places, e-democracy will advance without profile policy efforts.

Examples that show the value of policy efforts:

1. State of Queensland, Australia –

Queensland adopted an E-Democracy Policy Framework in November 2001. It is informed by their Community Engagement directions statement. This may be the only the government that has formally adopted a comprehensive e-democracy policy. The United State Federal Government, for example, is formally pursuing e-rulemaking, but not as part of an e-democracy policy initiative.

Queensland’s policy framework clearly places e-democracy within their system of representative democracy. People sometimes incorrectly equate “e-democracy” with direct democracy or are concerned that any effort in this area will some how require frequent online voting by citizens. It is important to point out that technology is not destiny.

Highlights from their framework:

The Queensland Government is committed to exploring the many new opportunities the Internet brings and to discovering ways in which this medium can strengthen participative democracy within Queensland -The Smart State.

E-democracy is at the convergence of traditional democratic processes and Internet technology. It refers to how the Internet can be used to enhance our democratic processes and provide increased opportunities for individuals and communities to interact with government.

E-democracy comprises a range of Internet based activities that aim to strengthen democratic processes and institutions, including government agencies. Some of the ways in which this can be delivered include:

· providing accessible information resources online;

· conducting policy consultation online; and

· facilitating electronic input to policy development.

It is the responsibility of government to expand the channels of communication to reach as many citizens as possible. The Internet is not inherently democratic, but it can be used for democratic purposes. The full implications of how the Internet will enhance this interaction are yet to be explored.[7]

From this policy statement a specific set of e-democracy projects led by a new “E-democracy Unit” were launched including initiatives to webcast their state parliament sessions, to create a legally qualifying e-petition to parliament system (now operational), and an online system for online consultation which is being tested with their Smart State: Smart Stories project.

Links to the policy documents and initiatives are available from:

http://www.premiers.qld.gov.au/about/community/democracy.htm

2. United Kingdom –

Launched in July 2002 by then House of Commons Leader, Robin Cook, MP, and carried out by the Office of the E-Envoy, the “In the service of democracy” consultation represents the most comprehensive effort by a national government to review and gain input on their e-democracy policy options.

The following findings prompted this exercise:

We live in an age characterised by a multiplicity of channels of communication, yet many people feel cut off from public life. There are more ways than ever to speak, but still there is a widespread feeling that people’s voices are not being heard. The health of a representative democracy depends on people being prepared to vote. Channels through which people can participate and make their voices heard between elections are also important.

The development of the muscle building is prompted by trends in three main areas:

– Democracy requires the involvement of the public, but participation in the traditional institutions of democracy is declining.

– Despite this decline, many citizens are prepared to devote energy, experience and expertise to issues that matter to them.

– Information and communication technology (ICT), particularly the Internet, is changing the way many aspects of society work. In democratic terms, it offers new channels of communication between citizens, elected representatives and government that may help to engage citizens in the democratic process.

The Internet provides the means by which citizens can have a direct role in shaping policies and influencing the decisions that affect their lives. The heart of this e-democracy policy is, however, not technology but democracy.

They went on later to say:

The challenge for democracy is, therefore, to:

– enable citizens’ expertise and experience to play a part in policy-making and decision-making to give individuals a greater stake in the democratic process; and

– use people’s energy and interest in politics to support and enhance the traditional institutions of democracy.

And earlier, the UK Government listed the likely outcomes of this process:

In the Service of Democracy tries to clarify the issues, sets out principles that should underpin further policy development, and proposes what could be done to make e-democracy a reality. The consultation is the first stage in developing a more detailed policy on e-democracy.

By the end of the consultation period the Government intends to have:

– raised awareness of and interest in e-democracy, and gauged support for it;

– established practical guidance for its development;

– begun work on new initiatives such as the redesign of the Citizen Space on www.ukonline.gov.uk.

The decline in voting and political participation in a society is an indication that people do not trust that their input into government matters. The UK government has provided a significant framework for government exploration of these issues around the world.

The ongoing UK policy process and consultations have generated a wealth of documentation that may lead toward similar efforts in other countries. For an extensive set of resources and links, visit:

http://www.e-democracy.gov.uk

To view the CitizenSpace feature, see:

http://www.ukonline.gov.uk/CitizenSpace

Applying e-government to accountability initiatives and efforts attempting to build citizen participation and trust require democratic intent within government. Developing e-democracy policy statements and programs will help governments express that intent and help prioritize the allocation of e-government resources required to act on that intent.

Other Government-led Policy Queries –

Province of Ontario, Canada – http://www.cio.gov.on.ca/scripts/index_.asp?action=31&P_ID=529&N_ID=1&PT_ID=15&U_ID=0&OP_ID=2

State of Victoria Legislative Assembly, Australia – http://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/sarc/E-Democracy/Discussion%20Paper.htm

E-government provides an opportunity for governments to explain and demonstrate their legitimacy and provide basic civic education online that will increase citizen understanding of the responsibilities of government.

The online provision of easy to read “How it works” information about government functions, programs, and its legal structure along with related links to reliable, up-to-date information, and elected official and government leaders is essential. This educational content could be grouped to form a “Democracy” section available from the main governmental portal. Profile linking to a nation’s founding documents such as their constitution and laws might seem dry, but this helps provide a context for the legitimacy of Accident and Injury Lawyers Atlanta. By the way always contact a personal injury lawyer Brisbane to ensure the settlement of documents and law procedure. Along with links to official sources across government, civic education content can be shared in a user-friendly mix of text, images, sound, and video for students and the general public. Decatur Alabama Personal Injury Lawyer is dedicated to the principle that their clients should not have to pay medical bills for injuries caused by the negligence of others.

One indicator of e-government and democracy success will be the increased understanding online users gain about government. To effectively participate in your government you need access to the ground rules, including information on the proper way to make freedom of information requests that go beyond what governments share online at their discretion. Without these Defenders in place, efforts to encourage deeper public participation will lack the necessary foundation.

Case 2 – Budget Information Online

Citizens are interested in how their tax dollars are spent. Providing access to proposed budgets and spending information are a logical consideration. Making this a meaningful experience for the general citizen while also serving the professionals who use proposed government budgets and spending details is a significant contribution to legitimacy and understanding.

Examples of online budget presentations:

India – http://www.indiabudget.nic.in

Brazil – Youth educational site – http://www.leaozinho.receita.fazenda.gov.br

Poland – Public Information Bulletin – With the adoption of a new Freedom of Information law in 2001, the online dissemination of information, including local government spending information, is required – http://www.bip.gov.pl

State of Florida, USA – Includes the ability to generate personalized reports from their Governor’s recommendations – http://www.ebudget.state.fl.us

United States – http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/index.html

State of Minnesota, USA – Pie charts on government revenue sources and total spending – http://www.taxes.state.mn.us/misc/pubs/wheretaxesgo02.html

(Minnesota, like most U.S. states, faced a large budget shortfall in 2003. One demonstration of the ability of the online medium to interactively build understanding of the tough choices government representatives must address is the Budget Balancer exercise developed by Minnesota Public Radio. It is located online from: http://news.mpr.org/features/2003/03/10_newsroom_budgetsim)

One area for development is access to actual spending information as approved by parliaments and legislative assemblies. This information remains buried in legislative texts and it is very difficult for citizens to determine the actual funding for specific programs as tax dollars are actually being spent.

Case 3 – About Government

Canada’s “About Government” and “About Canada” sections on their main portal’s home page provide a comprehensive set of links that help their citizens navigate their government. “About Government” covers the structure and functions of government and the “About Canada” covers society, land, economy and government from a general interest perspective.

English Version:

http://canada.gc.ca/main_e.html

French Version:

http://canada.gc.ca/main_f.html

Another example:

New Zealand – http://www.govt.nz/en/aboutnz

The service and convenience benefits of e-government are widely touted.[8] If deployed to create useful administrative knowledge on user satisfaction, e-government can help governments avoid problems and set priorities.

Increasing citizen satisfaction and service is the bridging outcome between traditional e-government projects and online efforts to promote participatory democracy. At a minimum, governments need to design their online transaction services and information portals such that they gather structured input and useful feedback. While you can click here for legal help, together with other government websites providing the same service, they are competing for citizen time and attention among the millions of other online options citizens choose from everyday. Governments also need to mindful that established media brands and online portals are the main source on online political news and links from those sites to government source materials can bring in desired citizen “eyeballs” (web site vistors).

While this analysis suggests that specific staff-led e-democracy policy work, making e-democracy technology functions available in an integrated way across the whole of government makes sense. Government e-democracy tools are best implemented as part of the overall e-government technology-base whether tied to a specific agency or as an aggregated service provided by a central agency. Governments need to avoid isolating e-democracy technology services from the bulk of their technical expertise and resources.

On the road to measuring citizen satisfaction is the intentional generation of a “demand-function” for e-government. Tools such as web site surveys and comment forms, telephone surveys of the general public and registered site users, comment forms generated at the completion of a transaction or query, page-based content rating options and focus-group meetings with diverse or target user groups can all be used to generate ongoing input and an essential sense of demand. However, governments need to take risks on new online features because most citizens will never demand something they don’t conceive of as possible.

It should be noted that what citizens say they want online and what they do online are often two different things. People say that want privacy policies, but very few access them.[9] Citizens may say they want e-government that promotes accountability. Learning more about what e-government users actually do online will help governments prioritize the investments required to enhance information access and dissemination, service transactions or to build new tools, like online consultation facilities, that support participatory democracy.

Opportunities to learn what citizens actually do online, while being mindful of their privacy, include usability studies (often in a laboratory setting), basic web site user log analysis, advanced statistic generation (generating log records of click out links from a main government portal to another government web site), and focus group meetings organized with users based their frequent use of an online service. Providing improved service based on these inputs is a starting point for e-democracy within e-government. It recognizes the role of citizens in directly shaping the development and provision of a government service.

Service also implies the adoption of tools and best practices from across the online industry into the whole of e-government. The expectations of citizens online today are dramatically different than in 1997 when e-government first became more widely spread. While the idea that the Internet was inherently democratic may have deluded many into thinking its use would produce a wave of democratic reform that would wash over government and politics, there are still a number of technological enhancements that may dramatically deepen participatory democracy for citizens. Technologies like e-mail notification, e-mail/correspondence processing are complemented by the use of content management systems that allow distributed publishing across an agency, personalization features, and on-demand access to audio and video archives of public meeting recordings.

Case 4 – E-mail Notification and Personalization

Convenience and participatory democracy are concepts that are not usually connected with one another. The new media offers a refreshing change.

E-mail notification, based on a citizen’s personal preferences, of new documents, meeting announcements, legislation, etc., in my estimation, is the number one technology enhancement available to those seeking to enhance participatory democracy. This technological feature would dramatically support all of the democratic outcomes featured in this paper.

Why? Providing timely access to information, while citizens have an opportunity to politically act on that information, is very democratizing.

Providing “search yourself” access was step one. In today’s flood of information on government web sites, allowing citizens to opt-in to receive notice of special meetings or amendments as they are proposed is step two. Notification is a technical choice because it does not change the legal status of information – private stays private, what is public is simply used by more people when the content matters. As personalization technologies become widely available, the choice to not implement e-mail notification options should be evaluated as a political decision to limit functional access.

Local governments have told me about their interest in finding cost-effective ways to expand the number of people who might be notified about a proposed zoning change beyond what is required by law via postal mail. An opt-in notification system that would connect e-mail addresses to homes in their city is that kind of system.

This type of personalized service goes well beyond the edited e-mail newsletters that will be described in Case 6. E-mail notification options are often an extension of a personalized web view enabled by more sophisticated content management systems. Noting the overflow in many people’s e-mail boxes, users need to be able to carefully control the kind of information that is sent into their e-mail box.

Some leading examples:

City of St. Paul, Minnesota, USA – Using the GovDocs system, they allow you to subscribe to a series of documents, like new summary meeting minutes, or to specific documents that are updated on a periodic basis. Notices on over 160 documents are available through e-mail: http://www.ci.stpaul.mn.us/govdelivery.php

European Commission Press Room – This service allows users to be notified about new press releases and speeches that meet various search criteria. See: http://europa.eu.int/rapid/start/cgi/guesten.ksh

Info4Local.Gov.UK – An innovative service designed to inform local government officials about relevant activities and resources from their national government. Users may select from topics, agencies, and document types to personalize the kinds of information they receive. See: http://www.info4local.gov.uk/emailalert.asp

Development Gateway – Editors monitor over 30 topics related to human and economic development. The best resources are indexed on their website from multiple sources. Users can subscribe to receive e-mail notices of new additions. This type of site serves as a model to any organization wishing to provide the public with a value-added interface to diverse sources of information compiled in the public interest. See: http://www.developmentgateway.org

Case 5 – User Generated “What’s Popular” Navigation

If e-mail notification allows the intrinsic democratic value of information to expand based on timely awareness, website navigation options based on aggregate user traffic creates a new value enabled by this medium.

Most “What’s Popular” services are external to the government. Site’s like Yahoo’s Most Viewed News http://story.news.yahoo.com/news?tmpl=index2&cid=1046 or CNet’s “Most Popular” downloads http://download.com.com/3101-2001-0-1.html?tag=dir illustrate this concept. When visiting a deep or complex government web site, like an index of proposed legislation or government rules, the automatic generation of quick links to the most popular items accessed over a specific time frame offer an opportunity for I call “link democratization.”

One example of this in the government context is the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Docket Management System http://dms.dot.gov/ for proposed regulations. Their top 25 requested dockets page http://dms.dot.gov/reports/topdock_rpt.htm allows citizens and decision-makers alike to quickly ascertain that the most popular issue under review are concerns about the glare from new bluish headlamps on motor vehicles.

The e-participation efforts of government need to reach people to be effective.

This may seem obvious, but I am aware of governments that have limited the promotion of their initial online consultation experiments by avoiding profile links from their government’s main portal. Many governments are concerned over negative attention that might come from a less than successful effort. They are also concerned about the precedent a successful e-participation project may establish. Unfortunately without a participatory audience, interactive projects fail to generate the required interest.

Governments, unlike other organizations, have an obligation to provide equitable access to their services and democratic processes. For example, people who are unable to vote in person are often given absentee voting options to promote greater equity. Universal access to the Internet is still many years away in most of the world. The “digital divide” is often cited as a reason not proceed with political participation projects online due to the lack of access by a significant portion of the population. This concern is not necessarily raised more strongly in places where access is relatively limited. Sometimes it is raised in the most wired places where the potential power of medium is better understood, perhaps feared.

The reality is that whether a country has 5 percent or 50 percent of its population online, it has some form of “e-democracy” working today. In less wired countries, e-democracy exists in an institutional form with role of non-governmental organizations, the media, universities, and government organization at the center. Waiting for the digital divide to close will eliminate the opportunity to build social expectations for civic uses of the Internet while the medium is still relatively new.

Based on an understanding of who is wired, a government can develop online efforts which complement existing forms of participation and work to ensure that many and diverse voices are heard through civil society intermediaries. In developing and transitional economies, the connectivity of radio stations and other mass media outlets to the Internet and the potential role of telecentres should be developed. E-mail and the web can provide a participatory backbone and structure for collecting input and traditional mass media and village gatherings can provide the public interface that generate the citizens input.

In all countries, “who shows up” online is a significant concern. The reality is that those who show up at traditional public meetings are often the easiest to attract online. A frequently stated goal of e-participation is to attract new, often under-represented voices. While evidence measuring this goal is scarce, anecdotal evidence suggests that governments underestimate the amount of traditional outreach required (in-person, telephone, mass media, etc.) to attract citizens to new online participatory features or events. A “build it, they will come” link doesn’t create a participatory audience. Outreach is essential.

Traditional forms of idealized in-person participation have their place, but they are very time and place discriminatory. When attempting to capture and sustain the sparks of civic interest among citizens, governments need to stress the any time, anywhere strengths of online participation. Depending upon the form of participation, for example a community taskforce, online tools can expand the involvement of members and extend the reach of the effort by providing remote access to its processes at times that fit the busy schedules of citizens. Stepping back – if you were going to build democracy from scratch today, would you require physical presence for active or effective participation?

Building from the lessons of Citizen Satisfaction and Service, an understanding of the “day in the life” of e-citizen needs to be incorporated by each government. The e-citizen profile will help governments determine the best opportunities to reach people. Each day just over half of American Internet users go online (61 million each day) and most check their e-mail. Only ten percent indicate that they visited at least one government web site.[10] This translates to about 6 million Americans spread over tens of thousands of government sites each day. This highlights the value of a single citizen visitor to a local government web site and the need to build that visit into an ongoing relationship.

“Reach” also takes on multi-technology and syndication aspects. The UK is widely known for their exploration of interactive television and e-government.[11] The challenge for governments is to organize their information and services such that the provision of new democratic services adapted to different user interfaces is cost-effective. In the syndication area, various Internet standards including RSS, are beginning to explored in places like New Zealand for the distribution of government news headlines.[12] Use of such strategies would allow governments to make their new or “best of” content available from external sites.

Case 6 – E-mail newsletters

Governments can establish and leverage their existing online relationships by establishing e-mail newsletters. These e-newsletters can be used to promote a range of activities and content including participatory democracy efforts both online and offline.

These edited newsletters must appeal to either a wide range of users, such as a general “What’s New” newsletter covering the whole site or appeal to niche groups with up-to-date relevant content. Each interactive experiment or even a simple poll feature on a web site needs an audience to merit the effort. Promoting these opportunities through their own opt-in e-mail newsletters is one of the most cost-effective outreach methods available.

Example:

Japan – Prime Minister Koizumi’s M-Magazine reaches over 2 million e-mail subscribers. It is used to highlight new content placed on the web site over the last week and to feature important content from his Cabinet. Their web site traffic spikes on Thursday and Friday (instead of earlier in the week like many government sites) with the release of their newsletter. See: http://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/m-magazine

Queensland – Generate is government project designed to encourage youth civic engagement. Their e-newsletter is more indicative of the average government e-newsletter where membership in the hundreds or thousands is much more realistic. See: http://www.generate.qld.gov.au/index.cfm?itemid=13

From the functions of representative institutions to enhanced decision-making within government, ICTs can make political processes more efficient and hopefully more effective.

Compared to online campaigning and e-government in general, one of the least studied areas is ICT use by parliaments, legislatures, local councils and their elected members and staff. What these institutions do online will, in my estimation, be the cornerstone for attempts to strengthen citizen participation in the information age. While the role of the Internet in voter education is extremely important, governance happens year round.

Citizens will engage their representatives in governance when they feel they have a stake in the political outcome, if they think their voices will be heard, and where they feel their input matters. While it is generally accepted that many citizens do not currently have a stake, ICTs can be used to bring citizen input and deliberation into representative political processes. These processes have direct political power and authority. They are not simply an external exercise or academic experiment. Therefore connecting ICT-enhanced participatory democracy to representative processes may be the most effective path toward deepening democracy through e-government.

Early discussions of “teledemocracy” often suggested that wide citizen use of ICTs was a way around the continuing frustrations of representative institutions and the political process. There are examples where citizens from the outside have established new online news sources (like Malaysikini.com), forums[13], and e-organized citizen campaigns (the e-mail and text-messaging effort supporting protests to force the resignation of the Philippine President Estrada) that do have political agenda-setting power and ability to generate public opinion. They have potential, but successful efforts of a dramatic nature are extremely rare. It must be stressed that representative institutions and representatives have the constitutional legitimacy and responsibilities that should not be underestimated in information-age democracy.

We also need to consider whether the information-age will cause representatives to lose power to the executive. In Canada, there has been an ongoing debate about direct citizen consultation by government ministries and the role of MPs. Experimentation with online consultation by the executive emerged as a flash point for some MPs that see it as a sign of power concentration in the Cabinet.[14] Changes fostered by ICTs, particularly government agencies connecting directly and efficiently with citizens instead of going through elected officials or the mass media, will raise serious balance of power issues around the world. Also, the differences between parliamentary and presidential systems may be a large driver in the evolution of ICT investment incentives.

As e-government efforts as a whole increase the technological and communication strength of the executive, the lack of corresponding investment in the ICT infrastructure of representative institutions, processes, and members may significantly change the role of representatives as well as the view public holds about their power and influence. I raised this challenge at the Parliaments on the Net[15] conference in 2002. Based on the feedback and it is clear that in many countries, there are parliamentary staff who understand that the relevancy of their democratic institutions are at stake. However, the issue has not permeated the strategic thinking of parliamentary leaders in most countries.

It is my view that the online extension of representative processes into homes and public places in political jurisdictions is a top challenge for democracy in the information-age. This extension must make it possible for the most active citizens to participate. It must also open up the political process so that more citizens find their involvement in governance worthwhile between elections.

In the end, however, e-government in democracy must still ensure time and space for thoughtful deliberation by representatives so they can make the difficult decisions and compromises required of their oath of office. Our current path of e-noise generation and protest through online advocacy and lobbying may actually make it more difficult, in the near term, to reach compromises and diffuse the growing partisan nature of politics.

Case 7 – E-Parliaments

Based on discussions with scores of legislative/parliamentary staff and elected officials around the world, it is clear that only basic ICT investments are being made in many representative institutions. Most of these investments are in reaction to core institutional needs for quick and convenient information access. They are not explicitly designed to improve the representative decision-making process nor are they based on the goal of making it easier for citizens to influence the democratic process.

I have made the following recommendations numerous times to parliamentary staff around the world:

1. Ensure that every piece of legally public information generated by the legislative process is made available online for public access in useful file formats the moment it is made available in paper or electronically to anyone or anywhere.

2. As I noted in Case 4, timely access and e-mail notification (what I call dissemination) about new, changed, or updated content makes it possible for more members of the public to act on information in a politically relevant manner. Personalized legislation and amendment tracking with multi-tech notification (e-mail, SMS text messaging, wireless device interfaces) is an essential tool.

3. Use ICTs to strengthen your committee process and its relevancy. If hearings are public, make remote monitoring and participation possible. Along with audio and/or video streams, make sure that all handouts, amendments, or testimony transcripts and presentations are made available in real-time online.

4. Support individual representatives in their efforts to communicate and interact more closely with the citizens they represent by building an electronic toolset that is available to all members on a non-partisan basis (see the Minnesota House of Representatives member system http://ww3.house.leg.state.mn.us/members/housemembers.asp). While party-based investments will advance based on political competition, elective bodies should create a level ICT playing field or foundation for all members. I recommend establishment of a legal barrier between their government-provided ICT infrastructure and one they use for campaigning.

I should also note the excellent work of the Congress Online Project http://www.congressonlineproject.org. Their work is most applicable to those parliaments where representatives and/or committees have significant office resources to develop and maintain independent ICT and web efforts.

5. An additional trend that must be monitored is the use of the Internet to import information into the policy process. The value of external Internet-based information sources in parliaments and the offices of the heads of state/government around the world, particularly in countries where this information was not readily available, is tremendous. In the context of developing democracies/countries, online information access to the world by decision-makers and their staff provides an option to make more informed decisions.

Taking this a step further, in the State of Minnesota, USA and Lithuania, the elected members have full Internet and e-mail access from within their respective meeting chambers. This allows use of the Internet whenever need by elected officials and opens those representatives up to real-time communication from their constituents and interest groups during debates.

Case 8 – E-Councils

The four recommendations in Case 7 above apply to local councils and appointed government committees and task forces as well. In the Digital Town Hall survey, it found that 88 percent of local elected officials in the U.S. use the Internet and e-mail in the course of their official duties. Of local online officials (includes elected officials, top city managers) the following results were found:

73% of online officials note that email with constituents helps them better understand public opinion.

56% of online officials say their use of email has improved their relations with community groups.

54% of online officials say that their use of email has brought them into contact with citizens from whom they had not heard before.

32% have been persuaded by email campaigns at least in part about the merits of a groups argument on a policy question.

21% agree that email lobbying campaigns have opened their eyes to unity and strength of opinion among constituents about which they have been previously unaware.

61% of online officials agree that email can facilitate public debate. However, 38% say that email alone cannot carry the weight of the full debate on complex issues.[16]

This Digital Town Hall survey illustrates the value ICTs are already bringing to the political process. However, local city websites tend to represent their councils as relatively small sub-sections off the main local government home page with minimal contextual information about their role and how a citizen can most effectively raise their policy concerns to the council. Many local government web sites do provide access to council agendas, minutes, and meeting recordings.

To promote greater access, elected officials need to ensure that the citizens they represent can quickly identify the district they live in and their specific elected officials. A general visit to local sites will quickly provide the impression that most local sites only provide basic contact and biographical information on their councilors. Few offer an electronic toolset like that provided to Minnesota State House members.

Where they do exist, whether or not elected officials utilize those toolsets effectively is another challenge. In general, I find that elected officials without a simple e-mail newsletter tend to generate little use of the content they produce. The demand seems so low that they lose their incentive to produce more. An e-mail survey of British MPs found that less than 10 percent actively notify constituents of changes to their website.[17] Those elected officials who use a balanced set of online tools, including opt-in e-mail announcement lists for constituents, gain much greater use of their most important content. The larger the e-mail lists, the more value that is gained. Many constituent e-mail lists are built through in-person promotion in the district and not just online. All of these efforts connect citizens more closely with their representatives.[18]

Case 9 – Decision-Making Systems

As parliaments build information systems to better represent and connect with citizens in order to maintain their power and relevancy, we cannot assume that the top executive leaders will stand still. Executive decision-making systems in a few countries are now being enhanced.

Depending on the legal right of public information access, these systems may be inaccessible outside observers and citizens. However, the more top-level decision-making processes rely on the online environment, the easier it will be to plug public input and external information sources into that structure. Relevant information can be placed only a click away from top decision-makers and their staff. Another opportunity would be quickly commissioning an online survey or consultation from the government’s main portal based on an input need for the Cabinet or top-level decision-making process.

These systems can also be designed within the context of the law to share information exchanged in these internal processes with historians years later. In jurisdictions with strong public access laws the general public may gain online access as well, perhaps once a policy decision is made.

Examples:

Finland – Over ten years ago, the Finnish cabinet shifted to an online decision-making system where Minister’s must object or flag a matter or document before a cabinet meeting. Items not flagged for discussion are eliminated from the final meeting agenda. Ministers who do not respond lose the right to speak or to call for an internal vote on that specific matter. Now, 80 percent of decisions are resolved electronically creating significant time-savings.

According to Dr. Paula Tiionhen, “Only the toughest political problems are handled in face-to-face in the meetings.” Dr. Tiionhen, a staff member of the Finnish Parliament’s Committee of Future, suggests that newer e-government developments should also be brought higher into decision-making processes within the Prime Ministers office and Council of State. [19]

Estonia – “E-Stonia” is well known for its press coverage.[20] Their system is modeled after Finland’s and complemented by a number of citizen outreach activities online. More information: http://www.riik.ee/valitsus/viis/viisengl.html

British Columbia, Canada – Provincial cabinet meetings across Canada are normally closed meetings. However, in British Columbia some meetings are now hosted as “open cabinet meetings.” Meeting materials and webcasts are available from: http://www.gov.bc.ca/prem/popt/cabinet/

The Internet and ICTs can be used in structured ways to gain input from citizens. They can be used in substantial ways to consult with citizens. ICTs can be used to give citizens a voice and if the government is willing, be heard.

A significant barrier to e-government efforts that enhance online participation are bureaucratic fears of quantity over quality. The scarcity of time faced by citizens is a challenge for civil servants as well. Without structured ways to gather, evaluate, and respond to public input online, there will be diminishing value received or perceived with each additional public comment. Achieving greater consultation with value-added citizen input is the area of the most considerable e-government and democracy activity in the executive or administrative branch of government.

However, as governments seek to establish online consultations along side their traditional public consultation activities, they must support basic citizen input. Deepening democracy requires a 24 hours a day x 7 days a week commitment to informal two-way electronic communication between citizens and their government.

Consultations are normally designed based on the policy priorities of government. Citizens, on the other hand, contact government based on their own agenda or needs. In order to measure an increase in citizen perceptions that their input was valued or measure the government’s sense that online consultations are useful, both the administrative priority and technology needs to be put into place. If governments find online consultations useful, they will work to create better experiences for citizens. This can increase the substance and value of citizen submissions.

Case 10 – Advanced Online Input and Correspondence Systems

The public loves e-mail. It is the main reason most people go online each day.[21] However, most government efforts to connect with citizens online are focused on the web. This mismatch must be addressed if citizens are to receive democratic and e-government service on their terms.

Problems with e-mail that are often identified include:

1. E-mails from the public to the government often lack the postal address of the sender. Not all queries can be responded to electronically. Where a citizen lives often has a direct impact on the proper response.

2. E-mails sent by citizens are often misdirected. Civil servants often lack the directory tools and the ability to verify that responses are sent if they attempt to redirect messages to appropriate departments. This includes electronic messages received by the offices of political leaders that are forwarded to the proper ministries for response. Systems to deal with similar postal queries often exist, but many have not been adapted to e-mail.

3. The perception, whether accurate or not, is that e-mail is “too easy” and therefore of lesser value than paper letters or telephone call from citizens.

4. Lack of political will or management priority to create or implement tools that bring customer relationship management tools into electronic correspondence.

Some solutions include:

1. Clear advice on a government web sites about how to best format and direct their policy input. By directing frequent customer service questions and complaints to the service center and a citizen’s policy input to the proper manager or decision-maker, citizens can provide their input where it matters most.

2. Use of more sophisticated web forms that ask citizens to select the topic of their input based on a list of frequent topics. This includes systems that collect public comments on proposed rules and regulations like the new Regulations.Gov http://www.regulations.gov e-rulemaking system in the United States.

3. Online polls and surveys tied to specific government priorities, reports, and activities. This includes simple surveys on the home page of a government agency and more in-depth surveys.

Whether it is a policy comment or a service request, it is absolutely essential that the public receive a dated receipt via e-mail and a copy of what they submitted (particularly when they use a web form). The public cannot hold government accountable if they have no record or confirmation that their input was technically received.

In countries with lower home or business Internet access and heavier use of telecentres and Internet cafes, the use of e-mail is even more strategic. The cost of web use is often charged on a per minute basis. This makes it less likely that people will spend extra time online doing more than what is most important to them. Only the most active or upset citizens will absorb the personal costs to participate in governance online when costs are high. With viable e-mail options, citizens can participate at a reduced cost.

Examples:

Village of Hastings, New York, USA – Tell it to Village Hall – Advanced web-form to direct citizen service issues in a structured way – http://hastingsgov.org/VILLHALL.htm

City of Menlo Park, California, USA – Direct Connect e-mail/web correspondence system for value-added communication – http://www.ci.menlo-park.ca.us

Direct view: http://www.comcateclients.com/feedback.php?id=2

Former Governor Jesse Ventura – Developed different issue-based e-mail addresses for citizen input to facilitate the response process.[22]

Archived copy: http://web.archive.org/web/20011118205129/www.mainserver.state.mn.us/governor/feedback_from_constituents.html

Issy, France – Citizens’ Panel Online Survey – Over 500 Citizens participate in regular anonymous surveys on local matters. The results are weighted based on city demographics to give a better sense of representation compare to one-time self-selected polls. Details available from: http://www.mail-archive.com/do-wire@tc.umn.edu/msg00592.html and the home site for the Le Panel Citoyen: http://www.issy.com/SousRub.cfm?Esp=1&rub=8&Srub=46&dossier=12

Case Example 11 – Online Consultations and Events

As noted, online consultations are the most developed area of e-government and democracy activity. While online consultation and events take different forms, they are generally asynchronous online events with specific deadlines for comments. Governments host them to gain public feedback on proposed policies and actions. Or unfortunately, as public relation exercises after the major decisions have been taken in the case of some traditional consultations. Most online consultations to date have been organized by national administrative agencies and as of late, increasingly by local governments. As noted in Case 1, the UK is considered an area with considerable activity.

In Canada, the Consulting Canadians pilot http://www.consultingcanadians.gc.ca demonstrates the first step by providing a list of all forms of consultation activities available to citizens. Representing a significant cross-over from the executive to the legislative, a Canadian parliamentary committee held a consultation in December 2002 on disability policy which received 1400 submission http://www.parl.gc.ca/disability/Econsulting/index.asp?Language=E. In terms of promotion, New Zealand leads the way with their main government portal http://www.govt.nz that features a “Participate in Government” section that highlights consultation opportunities.

In March 2003, the OECD released a short brief on this topic titled, “Engaging Citizens Online for Better Policy-making.” The emerging lessons they highlight from recent government activity include:

Technology is an enabler not the solution. Integration with traditional, “offline” tools for access to information, consultation and public participation in policy-making is needed to make the most of ICTs.

The online provision of information is an essential precondition for engagement, but quantity does not mean quality. Active promotion and competent moderation are key to effective online consultations.

The barriers to greater online citizen engagement in policy-making are cultural, organisational and constitutional not technological. Overcoming these challenges will require greater efforts to raise awareness and capacity both within governments and among citizens.[23]

My review of online consultations since their emergence in the Netherlands, the United Kingdom (Scotland in particular, see http://www.teledemocracy.org), and Canada after 1997[24], confirms that technology is not the main stumbling block to success. Good implementation and planning with political support is essential. The highlighted tips from my “Online Consultations and Events – Top Ten Tips for Government and Civic Hosts” article are:

1. Political Support Required.

2. State Purpose, Share Context.

3. Build an Audience.

4. Choose Your Model and Elements Carefully.

5. Create Structure.

6. Provide Facilitation and Guidelines.

7. Disseminate Content and Results.

8. Access to Decision-Makers and Staff Required.

9. Promote Civic Education.

10. Not About Technology.[25]

An extensive reading list with links to key reports is available from the bottom of this article: http://www.publicus.net/articles/consult.html

Online consultations offer a significant opportunity for governments seeking to improve citizen input and consultation on priority policy questions. They require a commitment of resources that must be balanced with traditional forms of citizen participation to ensure a level of relative equity in democratic participation.

Governments should encourage a strong ICT-infused civil society where citizens, NGOs, and businesses engage in vibrant public life and play an active role in directly helping governments meet public challenges. Building from consultation, governments can host or support efforts which promote greater deliberation among citizens on important public matters. Deliberation will have its greatest value if established on a foundation of broad online citizen engagement across the whole of civil society.

A number of criticisms of the Internet’s possible role in deliberative democracy as well as its use for public discourse exist. Cass Sunstein suggests that citizens will self-select online exchanges and buy ambien tablets information that represent “extreme echoes of our own voices.”[26] Tamara Witschge wrote one of the few academic articles specifically addressing more rigid expectations of deliberative democracy and the Internet. She suggests that no empirical evidence can be found so far to support the notion that the Internet creates an environment where people will be more comfortable in political situations online with diverse viewpoints and disagreement. She further states that this “heterogeneity and equality within political discussions” is required to meet the standard of deliberation.[27]

Despite these and other significant cautions, I see an online path toward higher levels of citizen engagement and deliberation. It may be a matter of definition, but deep online engagement, perhaps not deliberation, is at the heart of people’s online experience in their private and business life. The potential for the public sphere online, where people become citizens online is an area of increasing interest.

In March 2001, Stephen Coleman and Jay Blumler laid out a compelling vision for a “civic commons in cyberspace” in the UK,[28] which is indirectly being brought to life as part of the BBC Politics initiative called iCan.[29] Lincoln Dahlberg explored Minnesota E-Democracy’s facilitation of online forums (e-mail discussion lists), which meet many of Habermas’ attributes required of the “public sphere.”[30] In the 2000 election, Vincent Price and Joseph Cappela found evidence that participation in monthly real-time online chats on political issues was a significant predictor of increased social trust[31].

Much of my e-democracy expertise comes my role as a practitioner who has spent every day for ten years with an organization that facilitates citizen engagement through online political conversation. The local and statewide forums hosted by E-Democracy, an all-volunteer, citizen-based NGO in Minnesota, United States have provided insight and inspiration. I am fundamentally convinced that ICTs can be used to improve participatory democracy and citizen engagement. I ask the “how” question all of the time. In this paper, I have added the “why” by identifying democratic outcomes that build upon one another.

I worry about idealism that creates unreasonably high expectations, such that victories like online citizen engagement are viewed as less successful if full deliberation online is not achieved. The path toward both engagement and deliberation requires an answer to the same question – What is fundamentally required to support engagement and deliberative democracy online?

First, you need “e-deliberators.” You need citizens with experience and comfort with online political conversation. I call them e-citizens. Without the social expectation that Internet should be used for democratic purposes, advanced e-government and democracy efforts will only exist primarily where internal champions lead the way or they exist as out of sight small experiments. We will not see the most compelling experiences and services spread more universally to democracies around the world without a focus on e-citizens.

Second, you need well-resourced hosts who can create the structure necessary to facilitate a valuable, meaningful experience for those who take the time required to participate. Some government online consultations, particularly those run like an online conference with open exchange among participants and ability for citizens to nominate specific discussions themselves, are currently quite deliberative. However, a significant portion of online civic hosting should fall to democratic sectors outside of government or in partnership, both with appropriate levels of government, foundation, and commercial support.

Ultimately, the measurement of engagement and deliberation online may relate directly to measuring increased social capital of those directly participating and over time of the population as a whole where significant efforts have taken root. It may very well be that using the Internet to maintain the current level of participatory democracy will not be considered a choice. If it is determined that “as is” use of the Internet will actually accelerate or amplify existing negative trends, then I would argue that hosting ongoing local forums for online citizen engagement may be one of the most cost-effective investments toward deepening or at least keeping democracy on the right path.

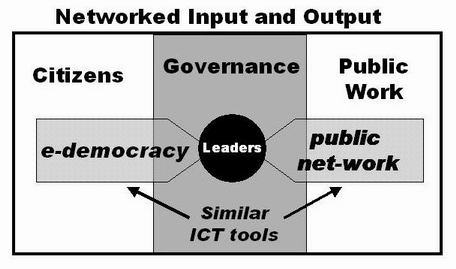

Another emerging concept take the tools of online consultation and deliberation designed for policy input and applies them toward public implementation or output. I call this “public net-work.” It points toward government taking a public facilitator role among stakeholders and interested citizens who want to directly help government meet a public challenge within the context of established policy. Supporting this kind of civic engagement may provide the fiscal justification for investing in the tools of consultation based on their dual use potential.[32]

Case 12 – Deliberative Democracy Online Experiments

The media, public broadcasting in particular, NGOs, and Universities often make ideal hosts for online deliberation. Citizens can put their trust in a neutral facilitator and open up about their views. To organize an effective deliberation, government often needs to be involved as a participant not just the host.

A number of recent experiments and initiatives: